Campaigns (17)

Protecting Powerful Owls

Coalition membership

The Powerful Owl Coalition is a group of concerned community environmental groups working in collaboration with the Powerful Owl Project of Birdlife Australia.

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

Protecting Powerful Owls

More information

Birdlife Australia's Powerful Owl Project

Download a flier and give it to your friends and neighbours to read

Download our position paper paper which is designed to educate and encourage all levels of government, professionals, groups, communities and individuals to protect and increase the number of Powerful Owls in urban areas

Powerful Owl Submission to the Sydney North Planning Panel on the Redevelopment of Hornsby Quarry (May 2020)

Email us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

Protecting Powerful Owls

Why they need our help

Human actions are causing a decline in numbers through development on bushland fringes, removal of trees and vegetation and road deaths

They are a threatened species — there may be as few as 5000 in the world

Their habitat supports amazing wildlife, enriches our lives and connects us with nature

Future generations deserve to see these birds in the wild

How you can help

Download a flier and give it to your friends and neighbours to read

Download our position paper paper which is designed to educate and encourage all levels of government, professionals, groups, communities and individuals to protect and increase the number of Powerful Owls in urban areas

Make your garden Powerful Owl friendly

Submit sightings to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. (give the time, date, place, any interesting details and, if possible, attach a photo or recording)

Contact your local council and politicians if you become aware of inappropriate development or clearing

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

Protecting Powerful Owls

How to make your garden owl friendly

Maintain and protect your old trees and value your trees hollows — they’re homes for frogs, possums, sugar gliders and birds

Install a nest box

Plant native trees and shrubs

Plant understorey trees and shrubs to support prey species

Plant shrubs in dense, continuous groupings for birds

Don’t plant climbers and plants close to trees as they can damage the bark

Keep thick mulch away from with tree trunks

Avoid changing soil levels under tree canopies to maintain healthy tree roots

Employ reputable arborists to prune trees (you may need council permission)

Plant a gum tree, but not too close to your house, for future generations of Powerful Owls – you will also enjoy its beauty, wildlife and shade

Protect Ringtail Possum dreys (they look like footballs made of twigs)

Reduce hard surfaces such as paving

Let’s enhance our lives too

Residential areas with mature trees and canopies are more desirable and therefore valuable, than those without

By planting and caring for your trees and shrubs you will:

- reduce the temperature of your home thus saving money on cooling

- beautify your home

- improve your streetscape

- increase the amenity of your local area

and all the while you will be protecting Powerful Owls! What’s not to like?

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

Protecting Powerful Owls

What do they need to survive?

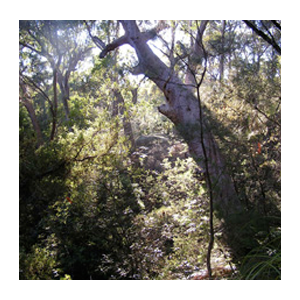

Huge old growth trees more than 80 cm in diameter, with hollow entrances of 40 cm or more

Roosting trees with dense canopies, particularly near rivers, creeks and gullies

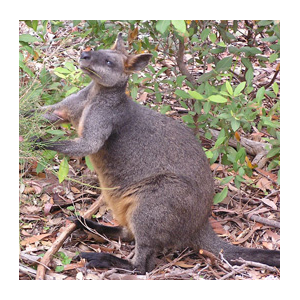

Foraging areas of complex vegetation large enough to support abundant prey species such as possums and birds

Urban green spaces, bushland and leafy gardens

Safe flight paths through bushland and urban areas

Humans to help them survive and thrive

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

Protecting Powerful Owls

Do you know that they ...

Are Australia’s largest owl

Are an icon of the Australian night

Are charismatic, impressive birds

Top predators which help to keep our ecosystems in balance, e.g. by controlling possum populations

Are only found along Australia’s east coast

Live for up to 25 years in the wild

Have long and strong partner bonds

Grow up to 60 cm in height

Have a wingspan of up to 140 cm

Have striking yellow eyes

Have large orange feet with strong, sharp talons

Have large orange feet with strong, sharp talons

Are brown and white with brown chevrons on a white chest

Chicks have downy white chests and grey masks

Nest in large hollows of trees over 150 years old

Have a delightful low ‘hoot hoot’

Need to eat approximately one possum (or flying fox) per night

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

Protecting Powerful Owls

Why they need our help

Human actions are causing a decline in numbers through development on bushland fringes, removal of trees and vegetation and road deaths

They are a threatened species — there may be as few as 5000 in the world

Their habitat supports amazing wildlife, enriches our lives and connects us with nature

Future generations deserve to see these birds in the wild

How you can help

Download a flier and give it to your friends and neighbours to read

Download our position paper paper which is designed to educate and encourage all levels of government, professionals, groups, communities and individuals to protect and increase the number of Powerful Owls in urban areas

Make your garden Powerful Owl friendly

Submit sightings to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. (give the time, date, place, any interesting details and, if possible, attach a photo or recording)

Contact your local council and politicians if you become aware of inappropriate development or clearing

This page is hosted by STEP on behalf of the Powerful Owl Coalition

History of the UTS Site

History of the UTS Site

The land was privately owned until 1915 when the Commonwealth Government acquired it during the First World War for the army’s use as a rifle range.

It was acquired by NSW in 1961 'for and on behalf of Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for the purposes of the Public Instruction Act of 1880'.

The site was developed as William Balmain Teachers College and opened in 1971. Construction had been delayed by protests by local residents about destruction of bushland on the site and later, with the backing of Ku-ring-gai Council, by protests about the problems of traffic in the narrow streets. The architect, David Turner, stated that his main design aim was to keep the college as compact as possible, because the landscape was so wonderful it should not have been built on. When it was going ahead anyway, I thought I’d protect the environment all I could'.

In 1974, along with the other teachers colleges, William Balmain Teachers College officially closed. It then became Ku-ring-gai College of Advanced Education, a corporate body with its own council. It was no longer tied to the Education Department. However it did not own the campus land which remained vested in the Crown.

UTS Aquisition, the Access Road and Railway Station Imbroglio

After changes in the education system, on 1 January 1990 the campus became part of UTS. The campus remained Crown land until they and the other universities involved finally acquired the titles which were issued on 1 December 1994 for a fee of $1. From FOI papers obtained it appears that title was only granted to UTS and the other universities on the condition that:

... the site continues to be used for the same academic purposes.

In 1990, UTS lodged a development application with council for construction of an access road from Lady Game Drive through the environmentally sensitive College Creek area. A committee was formed and STEP's representative, who has a civil engineering background, proposed an alternative route through a less sensitive area. Over the years UTS submitted several revised development applications, as a result of very protracted negotiations, community meetings and submissions involving UTS, Ku-ring-gai Council, the National Parks and Wildlife Service, environmental groups and residents. Eventually in 1998 Ku-ring-gai Council granted conditional development consent, demanding that UTS produced a much needed Bushland Management Plan for the grounds. However this never occurred and the development consent expired.

The cause was the Parramatta to Chatswood railway link and the proposal for a station at UTS, which would provide the additional access necessary and thus cancelled the need for an additional access road.

Unfortunately, the planning and review process for the rail link concluded that a station at UTS was not economically viable. UTS had prepared a forecast of an increase to 6600 students by 2006, however economic consultants for the Department of Urban Affairs and Planning indicated even an increase to 11,500 students would not make the construction financially viable.

Furthermore, the Environmental Impact Statement noted:

The UTS site is also located at the tip of a peninsula, with only one access point through surrounding residential streets, in a bush fire prone area. Some of the environmental planning issues associated with expansion of the campus on this site are able to be resolved, however the major concern of traffic and transport impacts on the adjacent area still needs to be addressed. The strong concerns and opposition of local councils and local residents over any proposed campus expansion is also a critical issue that needs to be noted.

Dilapidation of the Campus

After abandonment of the access road and railway station proposals, UTS stated that the campus was suffering because staff and students no longer wanted to go there. In June 2005, Fay Pettit was able to write:

There have been a great many indications that for some time the Ku-ring-gai campus is being deliberately run down and its education function undermined.

Fay went on to give nine examples including the exclusion of the campus from UTS annual reports, the withdrawal of lecturers, the closing down of the popular evening courses and the neglect of maintenance. The campus is now in a sad state of dilapidation: a state that one may conclude arose from the university wanting it that way.

Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act

In late 2005, the NSW Government amended the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act (1979) with the addition of Part 3A. The Environmental Defender's Office NSW published a paper which stated:

In effect, Part 3A of the Act dramatically reduces the involvement of the community in the original decision-making process and seeks to reduce any risk of concerned individuals or groups delaying or preventing significant development by limiting the grounds on which, or the circumstances in which, they can seek merits or judicial review. Instead, the Minister for Planning and the Director General, Department of Planning, maintain the power to make all key decisions regarding significant development, with advice from 'expert panels', limited input from other key agencies and little opportunity for effective criticism where the bureaucracy 'gets it wrong'.

In March 2007, CRI wrote to Frank Sartor, the Minister for Planning, requesting that he call in the UTS redevelopment and rezoning application using his powers under Part 3A.

STEP viewed this request as a tacit admission that the local community and Ku-ring-gai Council had rejected the proposal and thus these voices need to be sidelined.

On 14 June 2007, Frank Sartor registered the proposal as significant and pursuant to Schedule 1 of the State Environmental Planning Policy (Major Projects) 2005 and is thus declared as to be a project to which Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 applies. The Department of Planning thus listed the UTS development on their Register of Major Projects.

Stringybark Ridge

Stringybark Ridge, once the site of a long abandoned pony club, is part of the Berowra Valley National Park (BVNP). The main parties involved seemed then to be in agreement that this is how it should remain. All NSW national parks are governed by a legally binding Plan of Management (PoM).

Stringybark Ridge, once the site of a long abandoned pony club, is part of the Berowra Valley National Park (BVNP). The main parties involved seemed then to be in agreement that this is how it should remain. All NSW national parks are governed by a legally binding Plan of Management (PoM).

2005

After more than two years of community consultation with a wide range of local sporting and recreational groups, neighbours and other community groups a new Regional Park PoM was supported by both Hornsby Council and NPWS. This PoM stated that the main recreational use of the park was for bush walking, with some provision for limited dog walking on three management trails.

2006

Hornsby Council, after a careful review of potential sports grounds in the Shire, adopted a Sports Facility Strategy Plan, which specifically discounted the possibility of ever again using the old pony club site for active sporting purposes. All of which would seem to indicate that the future of Stringybark Ridge as an easily accessible urban lung for the local community, rather than as a basis for team sporting ovals, was assured.

2012

Despite the agreements reached above, then mayor, Nick Berman, unilaterally wrote to local state MPs asking for their support for the Stringybark Ridge site to be made available to provide additional team sporting facilities for soccer, cricket, AFL, netball and ‘other sports’, including attendant amenity blocks and spectator support arrangements and parking (see STEP Matters 165, p2–4 for full details of the ensuring events).

March 2015

NPWS issued a new draft PoM which, while specifically required under the relevant legislation ‘to protect and conserve’ the area, in point of fact proposed a spectacular reversal of their own previous policy.

Page 18 identified Stringybark Ridge as a potential area for a number of purposes, including ‘activities of a recreational, sporting, educational or cultural nature’ and Hornsby Council proposed building change rooms, amenities buildings, kiosks, parking and to erect tower lighting. The facilities would be used both mid-week and over weekends.

The draft PoM went on to state that NPWS would, in consultation with the community and Hornsby Council, prepare a precinct plan for Stringybark Ridge to articulate the specific activities and facilities for future use, including possible planned future use.

Our comments focused on our two main concerns, the proposed sporting fields on the two open grassed areas of approximately 2 hectares in size to the east of Schofield Trail, Stringybark Ridge, Pennant Hills and the potential mountain bike options for the park.

February 2023

The final PoM was adopted by the Minister for Environment and Heritage on 2 February 2023 ... an interval of eight years! In the PoM:

- the provision of sporting facilities has not progressed, but it has been identified as a potential site for recreational, educational and cultural activities

- other options include camping to support use of the Great North Walk and/or an area for community activities

We have many criticisms about the quality of the plan, for example the:

- geology section needs to be re-written with a correct balance between geology, landscape and soil

- naming and detail of species is inconsistent

- fish and mangroves are completely overlooked despite them being such important ecosystems

Click here for our response to the PoM.

A precinct plan is now being prepared to examine opportunities for future use and vegetation restoration. Vehicle and public access arrangements for Stringybark Ridge will be determined as part of the precinct plan.

STEP will be keeping an eye out for the precinct plan as our objection to sporting facilities was not about the sports per se but about the possible ecological impact of development.

STEP's Position

Undeveloped ridgetops are particularly rare and valuable in the valleys of the Lane Cove River and Berowra Creek, and we consider that the simple fact that it is a ridge makes Stringybark Ridge of conservation significance.

In 2015 STEP argued that the construction of sporting fields and mountain bike tracks would destroy the value of Stringybark Ridge as habitat and as a corridor. Stringybark Ridge is an integral part of the corridor from the Parramatta River to the Hawkesbury River as it the closest point to Lane Cove National Park. Nomadic and migratory fauna, as well as dispersing young, all need safe corridors for survival of the species.

UTS Ku-ring-gai Campus

From 1990, STEP was involved with the conservation of urban bushland at the University of Technology Sydney (Ku-ring-gai Campus) at Lindfield. Click here for some history of the site.

From 1990, STEP was involved with the conservation of urban bushland at the University of Technology Sydney (Ku-ring-gai Campus) at Lindfield. Click here for some history of the site.

In 2003, UTS announced its intention to cease using the site as a university and, in conjunction with CRI Australia, to seek rezoning for a residential development on the site of approximately 560 buildings. Ku-ring-gai Council refused the rezoning and the NSW Government took the issue out of Council’s hands. On 14 June 2007, Frank Sartor registered the proposal as significant and pursuant to Schedule 1 of the State Environmental Planning Policy (Major Projects) 2005 and is thus declared as to be a project to which Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 applies.

STEP's Position

STEP joined a committee, the Community Reference Group (CRG) which immediately expressed very serious concerns on numerous grounds. Although the CRG strongly opposed the proposal, UTS and the Government were able to say that the community had been consulted. The whole procedure, STEP’s position and the issues involved were summarised in STEP Matters (Issue 140, July 2007). Click here for a copy of our submission to the Department of Planning.

The Minister for Planning issued a determination on 11 June 2008. This approval entrenched the preferred project report submitted by consultants for UTS.

We lost a university and some bushland and gained dense housing in a precinct with high fire risk and poor road access. However over 9 hectares (22.6 acres) of bushland was transferred to National Parks. In addition, the community input succeeded in winning some improvements including a reduction in the number of dwellings approved for the site, the retention of a full-sized oval for community use and in retaining heritage buildings on the site.

The land was sold and is now being developed.

More...

Sydney Adventist Hospital Site

A Win for the Environment but expect Traffic Chaos

A Win for the Environment but expect Traffic Chaos

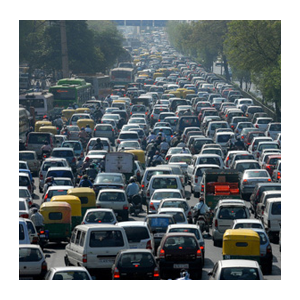

The Wahroonga Estate Concept Plan was approved by the NSW Minister of Planning on 31 March 2010. This approval brought to an end a saga that began in early-2007 with an initial submission from the developers that would have seen 2000 new residential dwellings, along with expanded schooling, nursing quarters, commercial and retail developments. It would also have meant a massive loss of bushland and many thousands of additional vehicle movements per day, dumped into an area already suffering from chronic peak time traffic congestion.

STEP was actively involved with this process (see below) which led to a significant reduction in the number of proposed residential dwellings and relocation of parts of the school. The development footprint was also scaled back so that the amount of conservation land was increased from 18 ha to 34 ha.

The Wahroonga Estate contains some magnificent bushland including endangered ecological communities such as Blue Gun High Forest and Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest and it has one of the finest examples of vegetation transition from shale to sandstone in northern Sydney. It is currently being well managed and restored by Wahroonga Waterways Landcare. In 2022 plans were submitted for the final stage of the development.

Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act

While STEP never had any problem with the hospital expansion plans, we did object to the significant over-development that the project represented for this particular site. Our concerns intensified when the developer, the Johnson Property Group, a major donor to State Labor, had the Minister call the project in under Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act in December 2007. This effectively removed the development from the decision making of the local community, but of course did nothing to remove the consequences of those decisions from having to be borne into the future by the local community.

Community Reference Group

STEP was appointed to the community reference group which was set up in March 2008 to provide at least the appearance of community consultation on the proposal. The group met five times during the course of the planning stage. STEP and other members of the group worked hard to highlight and identify both the environmental and infrastructural impacts and shortcomings of the various proposals.

This resulted in the matter being referred by the Department of Planning to the Commonwealth Department of the Environment as a ‘controlled action’ in relation to certain critically endangered ecological communities which were on the site.

Positive outcomes

STEP's detailed fact-based submission to the Department of Planning, was strongly supported by the Nature Conservation Council and the National Parks Association. It was also strengthened by an excellent submission from Ku-ring-gai Council. Both submissions challenged many of the inaccurate representations made in the Concept Plan. The developers were also criticised by the NSW Department of Environment and Climate Change regarding the proposed new school, which was, they said, 'poorly sited and planned'. The plans also attracted 160 local individual submissions from the public, of which over 96% were against the development proceeding.

In the end, these submissions resulted in a number of important changes:

- The number of private residential dwellings was reduced from 2000 to 500.

- Certain road links were removed.

- The school hall and oval were relocated.

- A lower scale of housing was decided for Mount Pleasant Avenue.

- The development footprint was scaled back.

- The amount of conservation land was increased from 18 ha to more than 30 ha.

- Half of the site was quarantined from development due to its ‘significant environmental value’ and the presence of endangered ecological communities such as the Sydney Turpentine Ironbark and Blue Gum High Forest. Importantly, this included the removal of the planned residential development on the east side of Fox Valley Road which has one of the finest examples of vegetation transition from shale to sandstone in the northern region of Sydney. The adjoining freeway corridor land to the north-east has a further 2 ha of Blue Gum High Forest/Turpentine-Ironbark Forest, while the lower riparian corridor links to the rare diatreme rainforest vegetation at Browns Field. This is indeed an environmental crown jewel worthy of special protection.

STEP commended both the developer and the SAN for their consideration of the environmental issues involved.

Negative outcomes

- The overall size and scale of the rest of the WER proposal did not alter much.

- The height limit for some buildings was increased to six stories and the retail and commercial expansion plans essentially remained as proposed.

- As the Planning Minister himself said when approving the project, it will become a whole new ‘mini suburb within a suburb’.

- The traffic infrastructure to support the new suburb remains a significant problem area and one without an apparent solution. With only some minor amendments to the original plan, the RTA and the developer believed that the road system was adequate for the proposed development once some upgrades were completed. It was clear that they had not addressed the issues raised in the detailed traffic report submitted by STEP, supported by an independent local traffic consultant. Indeed, the RTA sign-off for the development plan specifically excluded the need to upgrade the Pennant Hills Road/Comenarra Parkway intersection, which had previously been included by the developer's own traffic experts as needing upgrading!

St Ives Showground

In early 2010, Ku-ring-gai Council placed the draft options for St Ives Showground and precinct lands on public exhibition. STEP made the following points in its submission:

In early 2010, Ku-ring-gai Council placed the draft options for St Ives Showground and precinct lands on public exhibition. STEP made the following points in its submission:

- the need to protect in perpetuity the endangered ecological community known as Duffys Forest

- the removal of the Ku-ring-gai Mini Wheels Training Club (KMWTC) from this environmentally sensitive site

- the retention of the Wildflower Garden in its current location

In June 2010 Ku-ring-gai Council released a report which recommended a departure from the exhibited plan by retaining the KMWTC, despite recognising the widespread environmental damage being done. Indeed on this issue the report specifically noted the need ‘to carry out associated environmental management works to regenerate the Duffys Forest vegetation community’.

On the positive side, the report recommended that Duffys Forest and other existing natural vegetation be protected from encroachment, vehicles, compaction, nutrients, weeds and rubbish. Noting again, the exception of ‘the KMWTC area, which has been damaged over a long period of time. A separate plan will be devised to guide use in the KMWTC area.’

On 26 May 2015, Council adopted the draft St Ives Showground and Precinct Lands Plan of Management (dPoM).

In May 2017 Council commissioned a report on developing the tourism potential of the municipality. The report focused on a plan to redevelop the St Ives precinct to achieve a ‘wow factor’ to attract visitors, benefit residents and help grow the local visitor economy.

In 2021 a draft plan of management was released for St Ives Showground and Precinct Lands. Many community groups put in submissions prior to the deadline. However the papers for the council meeting that was to consider the draft PoM were published before the closing date. The report had obviously been written by council staff some days before. None of the submissions from the community groups were considered in the report. STEP and other groups protested about this treatment. Public consultation was a sham.

Roads

There is inherent conflict between the needs of the human population and the natural environment. We all live in houses on land that was once host to part of a natural ecosystem and we all travel on roads and railways that criss-cross the natural world and so compromise it. There are many more such examples.

There is inherent conflict between the needs of the human population and the natural environment. We all live in houses on land that was once host to part of a natural ecosystem and we all travel on roads and railways that criss-cross the natural world and so compromise it. There are many more such examples.

The issue at hand is not so much that we have such impact, humans have rights too, it is more that there are so many of us that our scale and rate of destruction is such that we have seen, and are facing more, widespread environmental degradation, animal and plant extinctions and other inexcusable consequences.

It is for these reasons that STEP has strong views on human population numbers and on the way that we interact with the remaining natural environment. Here we are talking about the part that freeway standard roads play in the overall problem.

Our planners have always made the basic and inexcusable mistake of building roads to solve existing congestion problems without any regard to the additional congestion those roads will cause. As John Norquist, the former mayor of Milwaukee and transport expert, said at the City of the Future conference in Brisbane at the University of Queensland in November 2010, 'building freeways in cities is like loosening your belt to deal with obesity'. We couldn’t have said it better.

We loosened our belt with the widening of the M2 tollway in 2011. Improved travel times will be nullified by demographic feedback as people take advantage of the improved road to travel more often, to travel closer to peak times and to live further away from their work. Congestion will quickly return and create the inevitable demands for more roads.

STEP has participated in the debate about expressway construction for 30 years. We were very involved in the campaign that resulted in the proposed expressway through the length of the Lane Cove Valley bushland being abandoned and have participated by responding to all proposals such as the original M2 and the proposed F3 to M2 and M7 link.

The debate is more than the environmental and social harm done by, or the practical futility of some road projects. It is about the sort of city that we want Sydney to be, about whether we really want to have 9 million people in another 50 years and 18 million in 100, about why we don’t build an integrated transport network with emphasis on rail and public transport, about why we don’t take demographic feedback into account in our planning and, crucially, why none of our politicians are prepared to address the longer term planning issues and why they cannot see that there cannot be infinite growth in a finite world.

We have assembled below our key road publications and submissions, along with other relevant references and shall add to them as time goes by.

F3 to M2 Link Proposal

In 2002 the RTA commissioned, on behalf of the Australian Government, a study to identify a route connecting the Western Sydney Orbital (M2/M7) to the F3, in Sydney's north, to relieve pressure on Pennant Hills Road and Pacific Highway.

The F3 to Sydney Orbital Link Study, carried out by consultants Sinclair Knight Merz (SKM) examined three corridors (Types A, B and C) and ultimately recommended that the preferred route follow the Type A Purple Option, linking the F3 to the M2 via an 8 km road tunnel beneath Pennant Hills Road, and this was duly accepted and endorsed in July 2004 by the Australian Government.

Significant objection and vocal opposition to the study's recommendations led to the 2007 Review of the F3 to M7 Corridor Selection by the Hon Mahla Pearlman AO, former Chief Judge of the NSW Land and Environment Court.

The Pearlman Report of September 2007 recognised changes in land use and transport flows since the study, however these reinforced the selection of the preferred route. The report also confirmed that assumptions and data used in the study were valid, and overall recommended that:

- the preferred route (the Type A Purple Option) 'be progressed to the next stages of investigation including: detailed concept design, economic and financial impact assessment'; and

- a Type C corridor be planned.

2008 saw many hysterical stories and editorials in local newspapers complaining about hold-ups on the F3 due to serious accidents and bushfires.

Ever since the original SKM study, local groups and identities – supported by the Pearlman Report (as an option after the tunnel link construction), the NRMA and a Sydney Morning Herald editorial in January 2008 – are calling for the construction of another freeway link from the Central Coast to the M7, crossing the Hawkesbury River west of the existing F3 crossing.

STEP's Position

STEP has always been aware of the danger to urban bushland posed by the old Lane Cove Valley freeway corridor. In recent years, we have continued to comment, preparing submissions for SKM's study and the Pearlman Report, as there are still vested interests lobbying for a surface route through the Lane Cove Valley and also because transport planning impacts on our present and future environment.

STEP is opposed to any F3 to Sydney Orbital link as will ultimately:

- increase traffic on the local road network in the long term

- encourage unsustainable car-dependent development in the region and particularly on the coast

- cause changes to travel behaviour that will increase air pollution in the Sydney Basin

- have the potential to destroy local bushland

We insist and recommend that nothing should happen until there is an integrated transport plan for NSW, and by this we mean that there must be an end to the continuous patching up of an ailing public transport and freight transport system, that factors such as population growth and impending peak oil should be assessed and a strategy developed to take us through the next 100 years.

- Lane Cove Valley Freeway Position Paper (1990)

- F3-M2 Proposed Link Position Paper (2002)

- Comment on the F3 to Sydney Orbital Link Study (2003, STEP Matters, Issue 119, p3)

- Submission on the F3 to Sydney Orbital Proposal (2003)

- Comment on the Outcome of the F3 to Sydney Orbital Study (2004, STEP Matters, Issue 124, p2)

- Submission to the Pearlman Review of the F3 to M7 Corridor Selection (2007)

- History of the Lane Cove Valley Freeway Proposals (2007, STEP Matters, Issue 142, p5)

- Update on the Issues Surrounding the F3 to Sydney Orbital Link (2010, STEP Matters, Issue 154, p6–7)

- Comment on the Proposed M2 Upgrade (2010, STEP Matters, Issue 155, p4–5)

Population

Position Paper on Population (2011)

Position Paper on Population (2011)- Australia’s Population hits 25 million but who is Cheering? (NMI Matters 199)

- Rapid Population Growth – Witches Hats Claim another Casualty (NMI Matters 183)

- Submission on the Issues Paper: A Sustainable Population Strategy for Australia (February 2011)

- Integenerational Report 2015: Why should Australia become so Big so Fast? (NMI Matters 180)

Many, perhaps most, media commentators and some environmentalists seem to believe that the population debate is all a dog-whistling exercise orchestrated by the bigoted and xenophobic. While there are of course some of those people around, that is far from STEP’s position.

The population debate is not about boat people, not about race, not about culture, not about religion, not about refugees in general and not about how many children one should have. It's a bigger issue. There can of course be rational discussion on all of those matters but they are peripheral to population.

We start from a world view where we see population heading to over 9 billion with much of it climbing rapidly out of poverty towards our level of consumption so that finite resources are being used up at an ever-increasing rate and huge natural areas being alienated to accommodate people. We see increasing rates of extinctions and the virtual impossibility of reducing the greenhouse effect in time to avert disaster. Jared Diamond's book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed informs us of the human race's dismal track record. We see the possibility, indeed the probability, of famine, war and massive dislocations.

At home we see that Australia's fragile environment is already highly stressed. We see cities like Sydney growing exponentially and using up farms and bushland while placing ever-increasing demands on scarce resources such as water. We see our mines sending ever-increasing supplies of coal that will add to world pollution and we see places such as the Barrier Reef degrading.

We also see our leaders, almost without exception, promoting never-ending GDP and population growth. We see the effective lobbying of churches and that of the BCA and its powerful members for exponentially expanding markets and consumption. And we see almost none of our leaders prepared to admit that there could be a problem looming or to discuss the issue.

We see that at our current rate of growth of about 2% per annum, Australia will have some 90 million people in 75 years and Sydney 18 million. With the lower rates of growth some are talking about it will take a little longer but the result will be the same.

So what is our vision?

We would like our leaders at all levels to openly discuss the issue. We want our leaders to appreciate that there cannot be infinite growth in a finite world and we would like them to plan to do something about it. It must be appreciated that there are many wealthy countries without increasing populations that are doing well and that per capita wealth, rather than GDP, is the real measure of financial well-being.

We have heard many politicians at the state and local level say that they cannot do anything about the problem because it's all the fault of the Federal Government. We see that as the ultimate cop-out. State and local government leaders have an obligation to engage the Federal Government on all issues affecting their domain. They engage with them on health, education, the Murray-Darling and other such issues. Would it not be negligent to not engage them also on population?